| Research Article | ||

J Microbiol Infect Dis. 2023; 13(3): 148-154 J. Microbiol. Infect. Dis., (2023), Vol. 13(3): 148–154 Original Research Bacteriological profile and antibiotic susceptibility of bacteria isolated from diabetic foot ulcers at the National Hospital of NiameyOusmane Abdoulaye1*, Souley Sanda2, Ahamadou Biraima1, Abdoul-Aziz Moumouni3, Mahaman Laouali Harouna Amadou1, Guiet Mati Fatima4, Saïdou Maman Sani Falissou1, Boukar Sidi Maman Bacha1, Boubou Laouli2 and François Tapsoba51Faculty of Health Sciences, Dan Dicko Dankoulodo University, Maradi, Niger 2Medical Biology Department, National Hospital of Niamey, Niamey, Niger 3Department of Internal Medicine, National Hospital of Niamey, Niamey, Niger 4Pharmacy and Traditional Medicine, Ministry of Public Health, Population and Social Affairs, Niamey, Niger 5Joseph Ki Zerbo University, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso *Corresponding Author: Ousmane Abdoulaye, Faculty of Health Sciences, Dan Dicko Dankoulodo University, Maradi, Niger. Email: ousmaneabdoulaye2010 [at] yahoo.com Submitted: 17/11/2022 Accepted: 12/08/2023 Published: 30/09/2023 © 2023 Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases

AbstractObjective: The objective of our work was to determine the bacteriological profile and antibiotic sensitivity of bacteria isolated from diabetic foot wounds. Methods: We conducted a descriptive cross-sectional study from July 1 to December 31, 2020. During this period, all diabetic patients with wounds were sampled. The different samples were plated on appropriate media. The identification of the isolated bacterial strains as well as the study of their sensitivity to antibiotics was performed according to conventional methods. Results: A total of 689 diabetic patients were followed during this period, 58 (8.41%) had infected foot wounds. The average age was 53.6 years with a sex ratio (M/F) of 1.15. Bacteriological analyses allowed the isolation of 48 bacterial strains (10 different species) with a predominance of Staphylococcus aureus (35.42%), followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae (20.84%), Escherichia coli (12.50%), and Enterobacter aerogenes (10.42%). We observed a predominance of Gram-negative bacilli (56.25%). The sensitivity tests performed on the identified bacteria showed that 100% of the enterobacteria strains were sensitive to ertapenem and imipenem, except for Proteus mirabilis. Four strains were tested for extended-spectrum betalactamase and none were producers. All Gram-positive cocci isolates were sensitive to vancomycin and resistant to penicillin G. Staphylococcus aureus strains were sensitive to erythromycin (82.35%), kanamycin (82.35%), and oxacillin (82.35%). Conclusion: These results show that diabetic foot wound infections are becoming more frequent. It is necessary to manage them with adequate antibiotic therapy based on an antibiogram to avoid the spread of multiresistant bacterial strains. Keywords: Diabetic foot, Bacteria, Antibiotic susceptibility, Niger. IntroductionThe diabetic foot represents all the cutaneous and osteoarticular lesions, secondary to the junction of neurological and/or arterial and/or infectious complications affecting particularly the distal extremities of the lower limbs in diabetics. It is a serious complication of diabetes. These lesions constitute germ entry points (Citron et al., 2007). In fact, nearly 25% of diabetics will develop these lesions during their lifetime. In 40%–80% of cases, these lesions become infected, significantly increasing the morbidity and mortality of patients. This is which constitutes a global public health problem (Sotto et al., 2008; Alassani et al., 2014; Alhubail et al., 2020). Diabetic foot osteitis is usually polymicrobial and Staphylococcus aureus is the most frequently isolated germ followed by Staphylococcus epidermidis. However, Streptococci and Enterobacteriaceae while anaerobes are more rarely found (Armstrong et al., 1996). Thus, the identification and study of the antibiotic sensitivity profiles of these germs is essential for better management of diabetic foot infections. It is in this context that we set ourselves the objective of determining the bacteriological profile and the sensitivity to antibiotics of bacteria isolated from diabetic foot ulcers. Materials and MethodsType and period of studyThis was a descriptive cross-sectional study. It lasted 6 months, from July 1, 2020 to December 31, 2020. Study settingOur study took place in Niamey, the capital of Niger. The geographical location and socio-economic characteristics of Niamey, give it a position of a crossroads and cosmopolitan city, thus, favoring the expansion of many infectious pathologies. Our study took place in three departments of the National Hospital of Niamey (HNN): the Endocrinology Department, the Biology Laboratory Department, and the Biochemistry Laboratory Department. Study populationThe study sample consisted of all diabetic patients with diabetic foot ulceration followed at the HNN. These patients had at least two local clinical signs of infection, had consented to the study, and for whom a bacteriological examination plus antibiotic susceptibility test of the foot ulcer was performed and the result validated. Inclusion criteriaOur study included diabetic patients followed at the HNN with diabetic foot ulceration with at least two local clinical signs of infection (swelling, redness, pain, heat, or suppuration), and who consented to the study. Sampling was comprehensive during the study period. VariablesTo achieve the study objectives, variables were identified. The variables age, sex, and origin provided information on the socio-demographic characteristics of the patients. The type of diabetes and the stage of the lesion according to the Wagner classification were important clinical data. The blood sugar level provided us with the status of the diabetes. The culture on the appropriate culture medium allowed us to assess the bacteriological yield. The germs identified gave us the status of the bacterial ecology of infected diabetic foot wounds. Antibiotic susceptibility testing of the isolated bacteria allowed us to establish antibiotic profiles. Data collection techniques and toolsA data collection form was designed to collect the information required for the study. The sociodemographic characteristics and clinical data of the patients were obtained through an interview with the patients and by the head physician of the endocrinology department or sometimes his assistant. The treatment record and the patient’s diary provided us with information on the current antibiotic therapy. The physician’s register allowed us to count the number of diabetic patients followed in the endocrinology department of the HNN. The blood glucose level and the result of the bacteriological examination of diabetic wound pus samples were obtained using medical laboratory techniques. Blood glucose procedureBlood sampling A dry tube venous blood collection was performed for each patient in our study. The tubes were labeled and then sent to the biochemistry laboratory. Blood glucose determination Blood glucose levels were determined on the patients’ sera, obtained after centrifugation of the clotted blood samples. Labeled hemolysis tubes: blank, standard, assay 1, 2, 3, each containing 1 ml of CYPRESS DIAGNOSTIC laboratory glucose reagent (glucose oxidase method), were placed on a rack. In the standard tube, 10 ul of the standard reagent was introduced. In the assay tubes, 10 ul of the serum of each sample to be assayed was put. The obtained solutions were mixed and incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes, staining stability for 40 minutes. The Mindrey BA-88A spectrophotometer (Fig. 1) was used to read the absorbances. The results expressed in mmol/l are displayed on the spectrophotometer interface. As soon as obtained, these results were validated through control samples and converted to g/l, then recorded on the survey sheets.

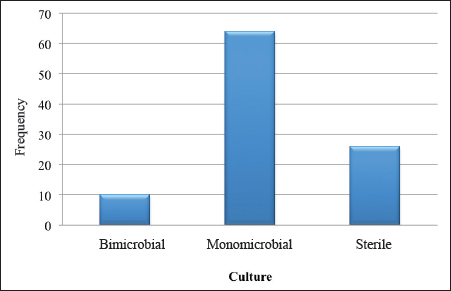

Fig. 1. Graphical representation of the samples according to the culture result. Procedure for bacteriological examination of diabetic foot pusIdentification by vitek 2 compact 15 Bacterial identification was performed using morphological, cultural, and biochemical characteristics of the bacteria. The following steps were followed:

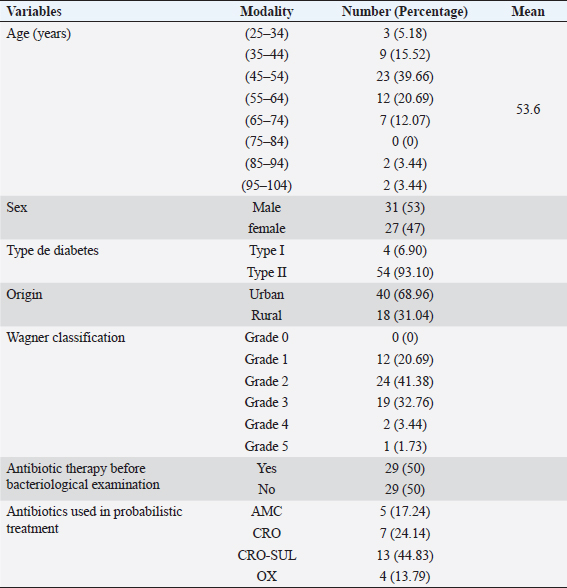

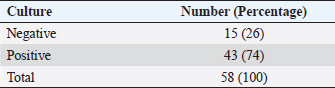

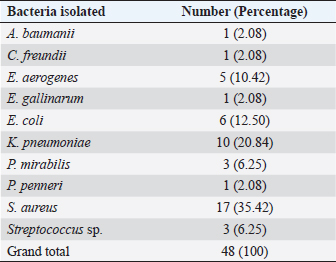

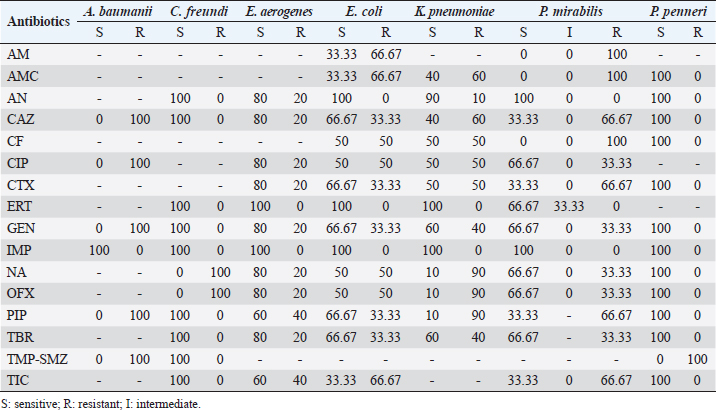

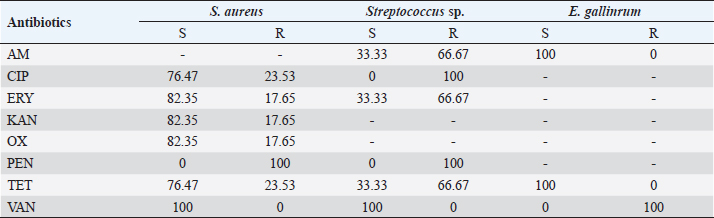

The vitek 2 compact 15 was used for the identification and antibiotic susceptibility testing of all Gram-negative bacilli and a large part of the Gram-positive cocci strains. The GN cards for Gram-negative bacteria and GP cards for Gram-positive bacteria contain the biochemical parameters that allow the identification of the isolated bacteria. The cards used by the vitek for the antibiogram contain the antibiotics to be tested according to the isolated bacteria. Gram-positive bacteria were tested with the AST-GP 75 card, containing twenty antibiotics: cefoxitin, ampicillin, oxacillin, gentamicin, streptomycin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, clindamycin, erythromycin, linezolid, daptomycin, vancomycin, doxycycline, tetracycline, tigecycline, nitrofurantoin, rifampin, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Gram-negative bacteria were tested with the AST-N233 card. This one contains eighteen antibiotics: ampicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, ticarcillin, piperacillin/ tazobactam, cefalotin, cefoxitin, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, ertapenem, imipenem, amikacin, gentamicin, tobramycin, nalidixic acid, ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, nitrofurantoin, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Detection of resistance phenotype In our study, the search for resistance phenotypes concerned enterobacteria resistant to third-generation cephalosporins (C3G) by the production of extended-spectrum betalctamase (ESBL) and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). Synergy test The synergy test was based on the partial inhibition of ESBL by penicillinase inhibitors such as clavulanic acid. The ESBL phenotype was tested on the susceptibility test by placing cefotaxime (30 μg) and ceftazidime (30 μg) discs 20–30 mm apart (center to center) from an amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (20/10 μg) disc. This showed (after incubation for 24 hours at 37°C) a clear increase in the inhibition diameter of the C3G-containing discs opposite the amoxicillin/clavulanic acid-containing disc, thus taking the form of a “champagne cork” for ESBL-producing strains. Cefoxitin test To detect meticillin resistance, the method consisted of depositing a cefoxitin disk (30 μg), on Mueller–Hinton agar seeded with heavy inoculum and incubated at 37°C. The reading is taken after 24 hours of incubation. Staphylococcus aureus characterized by inhibition diameters less than 24 mm, were resistant to meticillin. Data analysisExcel 2010 was used to record and process the data. Word software was used for document entry. Ethical approvalA research authorization was issued to us by the Director General of the HNN (Letter N°0158/DGHNNDAF/SGRH of June 16, 2020). The information given by each patient was completely confidential and would not be disclosed. It was only used for research purposes. ResultsSociodemographic, clinical, and therapeutic characteristicsThe sociodemographic, clinical, and therapeutic characteristics of our study population were as follows (Table 1). Bacteriological characteristicsDuring the study, 74% of positive cultures and 26% of negative cultures were obtained (Table 2). Figure 1 showed that 64% of the culture results were monomicrobial. Bacteria identified from samples of infected diabetic foot lesionsThe number of isolated and identified germs was 48, divided into 10 different species as shown in Table 3. During our study, 17 strains of S. aureus were isolated, i.e., 35.42%. Antibiotic susceptibilityThe majority of the Enterobacteriaceae strains showed very high levels of susceptibility to amikacin. Imipenem remained effective on all isolates tested. Also, we observed the emergence of betalactam-resistant strains (Table 4). Erythromycin, kanamycin, and oxacillin showed good activity on S. aureus. All isolates were sensitive to vancomycin and all the S. aureus series were resistant to penicillin G. Streptococcus spp. strains were sensitive to vancomycin (100%), resistant to ciprofloxacin (100%), and resistant to penicillin G (100%) (Table 5). DiscussionDiabetic foot ulcers are considered the most threatening and disabling complication of diabetes. An initial innocuous lesion may progress to chronic nonhealing wounds or gangrene that may require amputation of the toe, foot, or leg. Successful treatment of diabetic foot infections depends on proper clinical examination of the patient, isolation of pathogens, and identification of antibiotic susceptibility patterns. Table 1. Summary of sociodemographic, clinical, and therapeutic characteristics.

Our study involved 58 patients with an infected diabetic foot ulcer. In the present study, the mean age of diabetic patients with infected foot ulcers was 53.6 years. This result is similar to that of Lokrou and Dago (2008), in Côte d’Ivoire, who reported an average age of 56.8 years. In Morocco, Zemmouri et al. (2015) reported an average age of 64.4 years. In Turkey, Turhan et al. (2013) found 62 years of age. Both of these studies showed that wounds occurred earlier for patients in our study population, with the average age of lesion occurrence closer to that of Côte d’Ivoire. This could be explained by the much higher standard of living and quality of life in Morocco and Turkey compared to Niger and Cote d’Ivoire. Our study population was predominantly male (53.44%), with a sex ratio (M/F) of 1.15 in favor of men. In Niger, Sani et al. (2010) reported a rate of 71.1% for the male gender. Guira et al. (2015) found a sex ratio of 1.37 in Burkina Faso. This male predominance could be explained by the hygiene and assiduity of foot and body care in general. Indeed, naturally, women are much more careful about body hygiene and are, therefore, less exposed to the risks of diabetic foot infections. Table 2. Distribution of samples according to bacteriological performance.

The blood glucose level measured before the pus was collected for bacteriological examination showed that 82.76% of the study population had a blood glucose level above the normal value (1.26 g/l). The mean blood glucose level of the patients was 2.5 g/l, with extremes ranging from 0.35 to 5.10 g/l. In Togo, Djibril et al. (2018), reported a mean blood glucose level of 2.10 g/l with extremes of 2.10 and 4.11 g/l. These high blood glucose levels observed in our study population could be explained by a lack of follow-up or poor therapeutic follow-up, and consequently the occurrence of complications, including diabetic foot infection. In our study, 68.96% of patients with an infected diabetic foot ulcer were from urban areas, a result similar to that found in the study by El Hariri (2008), in Morocco. The frequency of patients with infected diabetic foot ulcers coming from urban areas could be explained by the proximity and accessibility to hospitals with specialized services for the management of diabetes and its complications. Indeed, due to the high cost of diabetic foot care, very few patients in rural areas have the opportunity to be followed in a specialized service. Table 3. Distribution of samples according to bacteria identified.

Culture of pus specimens on appropriate medium revealed that 64% of cultures were monomicrobial, 10% polymicrobial, and 26% sterile. These results are similar to those of Turhan et al. (2013), in a similar study conducted in Turkey which reported a rate of 65% monomicrobial, 15% polymicrobial, and 20% sterile cultures. The high rate of monomicrobial culture observed could reflect the reliability of our samples. Víquez-Molina et al. (2018) had isolated S. aureus only in 26.64% of 379 patients with an infected diabetic wound. However, the predominance of S. aureus in diabetic foot infections has been reported in Burkina Faso, Kuwait and Los Angeles, USA (Guira et al., 2015; Kwon and Armstrong, 2018; Alhubail et al., 2020). The high rate of S. aureus isolates could be explained by the proximity of wounds to the skin and external mucosa, which naturally inhabit Staphylococcus in its commensal form. In fact, the transition to the pathogenic form is favored in diabetic patients by a decrease in immune defenses and a high level of sugar in the blood. Table 4. Susceptibility profile of Gram-negative bacteria isolated from diabetic foot ulcers.

Table 5. Susceptibility profile of Gram-positive bacteria isolated from diabetic foot ulcers.

The sensitivity tests performed on the bacteria identified during our study revealed that 100% of the series of Enterobacteria were sensitive to carbapenems (ertapenem and imipenem) except for Proteus mirabilis, which showed an intermediate sensitivity of 33.33% to ertapenem. Absolute sensitivity of Enterobacteriaceae was also observed toward amikacin. These results are similar to those of Turhan et al. (2013), in Turkey and Jadid (2015) in Morocco, who demonstrated the activity of these three molecules on Enterobacteria strains. Indeed the absolute sensitivity of Enterobacteria strains toward these molecules, observed in our study, could be explained by their low prescription by clinicians. Indeed, due to their high cost, and to preserve them from acquired resistance, these molecules are most often prescribed as a last resort. An emergence of resistant strains of Enterobacteria was observed during our study. All strains of P. mirabilis were resistant to ampicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, and ticarcillin. Ninety percent of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates were resistant to nalidixic acid, ofloxacin, and piperacillin. These antibiotics were highly prescribed, widely available, and accessible outside of formal pharmaceutical management frameworks, resulting in indiscriminate use. All strains of S. aureus were susceptible to vancomycin. Streptococcus spp. strains were sensitive to vancomycin (100%). In the study by Turhan et al. (2013), vancomycin was active on all Gram-positive cocci. We observed that penicillin G had no activity on the Gram-positive cocci isolated in this study. Also, Streptococcus isolates were consistently resistant to ciprofloxacin. This emergence of CGP strains resistant to these two molecules could be explained by the excessive use of the latter. In a series of four isolates of Enterobacteria tested, no ESBL were identified. Three strains or 17.65% of the S. aureus isolates isolated in our study were resistant to methicillin. In the study by Guira et al. (2015) in Burkina Faso, there were neither MRSA nor ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae among the isolated strains. Our study was limited to the most sought-after bacteria in laboratory routine including aerobes and aero-anaerobes. Thus, with a sterile culture result of 26% in the context of clinically established infections, the search for other pathogens such as anaerobic bacteria, parasites, dermatophytes, and viruses is necessary. ConclusionDiabetic foot infection remains a serious complication of diabetes. Optimal antibiotic therapy is one of the key elements of management. It requires monitoring of bacterial epidemiology and accurate documentation of the infection. In our study, the incidence of diabetic foot infection was 8.41%. Diabetic foot infection was dominated by Gram-negative bacilli (K. pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Enterobacter aerogenes, P. mirabilis, Citrobacter freundii, Acinetobacter baumanii, and Proteus peneri); however, the most frequently isolated species was S. aureus. The isolated bacteria had shown a high rate of sensitivity to antibiotics. In addition, an emergence of resistant bacteria was noted. Knowledge of the microbiology of diabetic foot infection is essential. It conditions the choice of targeted antibiotic therapy and contributes to improving the quality of the management of this disease and reducing the emergence of antibiotic resistance. Based on the results of our study, empirical antibiotic therapy for diabetic foot infection should provide coverage for S. aureus, streptococci, and Enterobacteria. AcknowledgmentsThe authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the management of HNN for their support. The authors are grateful to the patients who agreed to participate in the survey for their cooperation. Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. ReferencesAlassani, A., Gninkoun, J. and Djrolo F. 2014. Bactériologie des infections du pied chez les diabétiques à Cotonou. RAFMI 1(2), 1–44. Alhubail, A., Sewify, M., Messenger, G., Masoetsa, R., Hussain, I., Nair, S. and Tiss, A. 2020. Microbiological profile of diabetic foot ulcers in Kuwait. PLoS One 15(12), 1–15. Armstrong, D.G., Lavery, L.A., Sariaya, M. and Ashry, H. 1996. eukocytosis is a poor indicator of acute osteomyelitis of the foot in diabetes mellitus. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 35(4), 280–283. Citron, D.M., Goldstein, E.J., Merriam, C.V., Lipsky, B.A. and Abramson, M.A. 2007. Bacteriology of moderate-to-severe diabetic foot infections and in vitro activity of antimicrobial agents. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45(9), 2819–2828. Djibril, A.M., Mossi, E.K., Djagadou, A.K., Balaka, A., Tchamdja, T. and Moukaila, R. 2018. Pied diabétique: aspects épidémiologique, diagnostique, thérapeutique et évolutif à la Clinique Médico-Chirurgicale Du CHU Sylvanus Olympio de Lomé. Pan Afr. Med. J. 30, 4; doi:10.11604/pamj.2018.30.4.14765 El Hariri, M. 2008. Pied diabétique le pied diabétique: étude épidémiologique et prévention. Doctoral Thèse, CHU Med VI de Marrakech, Marrakech, Morocco. Guira, O., Tiéno, H., Traoré, S., Diallo, I., Ouangré, E., Sagna, Y., Zabsonré, J., Yanogo, D., Traoré, S.S. and Drabo, Y.J. 2015. Écologie bactérienne et facteurs déterminant le profil bactériologique du pied diabétique infecté à Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso) 2015. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 108, 307–311. Jadid, L. 2015. Aspects microbiologiques des prélèvements au cours des infections du pied diabétique: Étude rétrospective sur cinq ans à l’HMIMV (2009-2014). Thèse, Université Mohammed V-Rabat, Rabat, Morocco, 144p. Kwon, K.T. and Armstrong, D.G. 2018. Microbiology and antimicrobial therapy for diabetic foot infections. Infect. Chemother. 50(1), 11–20. Lokrou, A. and Dago, K.-P. 2008. Stratégie d’amelioration de la prise en charge du pied diabétique en Côte d’Ivoire. Méd. Mal. Metab. 2(2), 185–187. Sani, R., Ada, A., Bako, H., Adehossi, E., Metchendje Noundui, J. and Baoua, B.A. 2010. Le pied diabétique: aspects épidémiologiques, cliniques et thérapeutiques à l’hôpital national de Niamey: à propos de 90 cas. Méd. Afr. Noire 57(3), 172–176. Sotto, A., Lemaire, X., Jourdan, N., Bouziges, N., Richard, J.-L. and Lavigne, J.-P. 2008. Activité in vitro de l’ertapénème vis-à-vis de souches bactériennes isolées de plaies infectées du pied chez des patients diabétiques. Méd. Mal. Infect. 38, 146–152. Turhan, V., Mutluoglu, M., Acar, A., Hatipoglu, M., Onem, Y., Uzun, G., Ay, H., Oncul, O. and Gorenek, L. 2013. Increasing incidence of Gram-negative organisms in bacterial agents isolated from diabetic foot ulcers. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 7(10), 707–712. Víquez-Molina, G., Aragón-Sánchez, J., Pérez-Corrales, C., Murillo-Vargas, C., López-Valverde, M.E. and Lipsky, B.A. 2018. Virulence factor genes in Staphylococcus aureus isolated from diabetic foot soft tissue and bone infections. Int. J. Low. Extrem. Wounds 17(1), 36–41. Zemmouri, A., Tarchouli, M., Benbouha, A., Lamkinsi, T., Bensghir, M., Elouennass, M. and Haimeur, C. 2015. Profil bactériologique du pied diabétique et son impact sur le choix des antibiotiques. Pan Afr. Med. J. 20, 148; doi:10.11604/pamj.2015.20.148.5853 | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Ousmane A, Souley S, Ahamadou B, Abdoul-aziz M, Laouali HAM, Fatima GM, Saïdou MSF, Boukar SMB, Boubou L, Francois T. Bacteriological profile and antibiotic susceptibility of bacteria isolated from diabetic foot ulcers at the National Hospital of Niamey. J Microbiol Infect Dis. 2023; 13(3): 148-154. doi:10.5455/JMID.2023.v13.i3.7 Web Style Ousmane A, Souley S, Ahamadou B, Abdoul-aziz M, Laouali HAM, Fatima GM, Saïdou MSF, Boukar SMB, Boubou L, Francois T. Bacteriological profile and antibiotic susceptibility of bacteria isolated from diabetic foot ulcers at the National Hospital of Niamey. https://www.jmidonline.org/?mno=302657410 [Access: July 03, 2025]. doi:10.5455/JMID.2023.v13.i3.7 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Ousmane A, Souley S, Ahamadou B, Abdoul-aziz M, Laouali HAM, Fatima GM, Saïdou MSF, Boukar SMB, Boubou L, Francois T. Bacteriological profile and antibiotic susceptibility of bacteria isolated from diabetic foot ulcers at the National Hospital of Niamey. J Microbiol Infect Dis. 2023; 13(3): 148-154. doi:10.5455/JMID.2023.v13.i3.7 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Ousmane A, Souley S, Ahamadou B, Abdoul-aziz M, Laouali HAM, Fatima GM, Saïdou MSF, Boukar SMB, Boubou L, Francois T. Bacteriological profile and antibiotic susceptibility of bacteria isolated from diabetic foot ulcers at the National Hospital of Niamey. J Microbiol Infect Dis. (2023), [cited July 03, 2025]; 13(3): 148-154. doi:10.5455/JMID.2023.v13.i3.7 Harvard Style Ousmane, A., Souley, . S., Ahamadou, . B., Abdoul-aziz, . M., Laouali, . H. A. M., Fatima, . G. M., Saïdou, . M. S. F., Boukar, . S. M. B., Boubou, . L. & Francois, . T. (2023) Bacteriological profile and antibiotic susceptibility of bacteria isolated from diabetic foot ulcers at the National Hospital of Niamey. J Microbiol Infect Dis, 13 (3), 148-154. doi:10.5455/JMID.2023.v13.i3.7 Turabian Style Ousmane, Abdoulaye, Sanda Souley, Biraima Ahamadou, Moumouni Abdoul-aziz, Harouna Amadou Mahaman Laouali, Guiet Mati Fatima, Maman Sani Falissou Saïdou, Sidi Maman Bacha Boukar, Laouli Boubou, and Tapsoba Francois. 2023. Bacteriological profile and antibiotic susceptibility of bacteria isolated from diabetic foot ulcers at the National Hospital of Niamey. Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 13 (3), 148-154. doi:10.5455/JMID.2023.v13.i3.7 Chicago Style Ousmane, Abdoulaye, Sanda Souley, Biraima Ahamadou, Moumouni Abdoul-aziz, Harouna Amadou Mahaman Laouali, Guiet Mati Fatima, Maman Sani Falissou Saïdou, Sidi Maman Bacha Boukar, Laouli Boubou, and Tapsoba Francois. "Bacteriological profile and antibiotic susceptibility of bacteria isolated from diabetic foot ulcers at the National Hospital of Niamey." Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 13 (2023), 148-154. doi:10.5455/JMID.2023.v13.i3.7 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Ousmane, Abdoulaye, Sanda Souley, Biraima Ahamadou, Moumouni Abdoul-aziz, Harouna Amadou Mahaman Laouali, Guiet Mati Fatima, Maman Sani Falissou Saïdou, Sidi Maman Bacha Boukar, Laouli Boubou, and Tapsoba Francois. "Bacteriological profile and antibiotic susceptibility of bacteria isolated from diabetic foot ulcers at the National Hospital of Niamey." Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 13.3 (2023), 148-154. Print. doi:10.5455/JMID.2023.v13.i3.7 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Ousmane, A., Souley, . S., Ahamadou, . B., Abdoul-aziz, . M., Laouali, . H. A. M., Fatima, . G. M., Saïdou, . M. S. F., Boukar, . S. M. B., Boubou, . L. & Francois, . T. (2023) Bacteriological profile and antibiotic susceptibility of bacteria isolated from diabetic foot ulcers at the National Hospital of Niamey. Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 13 (3), 148-154. doi:10.5455/JMID.2023.v13.i3.7 |